WALNUT TREES FOR NUT

THE MOST PROFITABLE ALTERNATIVE

Meristec proposes one of the most profitable farming alternatives in Spain: walnut trees for nut production. One of the most consumed fruits in the world, among which there is a wide variety on offer that requires adequate selection, correct plantation design and an essential tree formation in order for it to be productive.

The varieties of walnut are classified by their capacity of fructification in:

Production on the tree’s periphery that needs large size to achieve high yield levels. Its production ceiling is low (2,500 Kg/Ha, 3,000 in exceptional cases). FRANQUETTE and/or Hartley are terminal variaties.

Traditional variety, the most used in France. It undergoes terminal bearing, which limits its productive ceiling. Late catking and female flower blooming. Its use in France has been widespread, since its late leafing makes it less sensitive to spring cryptogamic diseases (bacteriosis, anthracnose). It requires extra-late pollinators, such as Ronde de Montignac or Meylannaise. Excellent walnut quality.

Production in the buds of each branch, for which it is not necessary to increase its size. Its productive ceiling is high (reaches up to 8,000 Kg/Ha depending on conditions). Its terminal varieties are CHANDLER, VINA, HOWARD, TULARE, LARA, SERR, SUNLAND, FERNETTE® and FERNOR®.

Variety selected by the University of California (UC Davis) in 1979, highly appreciated due to the great quality of its fruitnut: large, smooth, good sealing and very light grain colour. Moderate sensitivity to bacteriosis and highly fruitful. It reaches 80-90% lateral bearing. The tree is of medium size and vigorous. Harvests medium-late and needs Fernette, Franquette or Cisco as pollinators. It is the first recommended variety for non-planted orchards. Chandler is not advisable under three circumstances: if there not enough chilling (approximately 800 h), if the summer temperature is usually not above 25-30°C, and the risk of late spring frost extends later than the 2nd week of May.

Exceptionally productive tree. It produces 80-90% of lateral bearing. Its nut is large with a light grain colour and good sealing. Both leafing and harvesting are medium-early and can be pollinated by Tehama, Chandler or Howard. A disadvantage is its high sensitivity to bacterial blight and sunbum. Therefore, it is a tree that isn’t very weepy which makes it difficult to train in a central leader.

It is part of the same selection of UC Davis in which Serr, Chandler, Sunland or Tulare were obtained. Midseason Harvest (between 7 and 10 days before Chandler), which makes it better when many hectares of that variety have already been planted. It has 80-90% lateral bearing. It leafs before Chandler, and its nut is big land well sealed. Its grain is 90% clear and has a very good fruit quality. Small to medium-sized tree which is difficult to grow due to its low vigor. It makes it suitable for high density hedgerow orchards (7×3.5 m), where it can be very fruitful (from 6 to 6,500 Kg/Ha). Suitable pollinators: Fernette, Franquette or Cisco.

Variety obtained by the UC Davis breeding program in 1979. Very vigorous tree of the Serr genetic line, which has been used in intensive orchards with irregular results. Less chilling requiring (600-650, at Howard level). Very fruitful, with good quality large-calibre walnut and grain filling, although its shell is quite rough and the colour of its grain is darker than that of Chandler, which makes it less appreciated on some markets. Leafing date is onea week before Chandler that requires the same pollinators. An alternative to Chandler to prevent problems during harvesting, as it ripens a week before. Not recommended in areas with potential early frosts in autumn, as its extreme vigor makes it difficult to vegetatively stop and the risk of damage by frost is very high. Nor in areas prone to potential late frosts in spring.

Variety obtained by a French nursery owner, although its origin seems to have a close relationship with the UC Davis breeding program. Leafing date is mid-April. Mid quality nut, interesting mainly for green walnut production. It is used in very intensive orchards, with high yields. The pollinators are the same as for the Chandler group. Its use is recommended in areas where summer temperatures are not high enough for Chandler to grow well (25ºC maximum or lower). Meristec doesn’t produce it yet.

Californian variety obtained by Serr and Forde in UC Davis. Large nut with clean seal and very high yield. Large and extremely vigorous tree, early ripening and leafing with high resistance to winter cold (but not frost). It produces 65% of lateral bearing. Its pollinators are Chico, Pedro and Tehama. It is not recommended in areas with potential late spring frosts, in addition to being sensitive to sunburn. It has a high kernel performance, which makes it the most recommended for kernel production. PFA (Pistillate Flower Abortion) sensitive variety: a problem related to an excess of pollen.

It has been selected as a pollinator. Franquette x Lara cross. Medium vigor and it adapts well to hedgerow orchards. It undergoes lateral bearing, although it produces a yield slightly lower than the base variety. Late leafing and good nut quality. It can be marketed without problems when mixed with its base variety. High chilling requirements. This variety is a very good pollinator for Chandler and its group (Howard, Tulare), as it produces catkins very early (they start being seen in the 2nd year of grafted plants of 2 + 1). Variety registered by INRA (French National Institute for Agricultural Research).

Franquette x Lara cross. Medium vigor and its bearing is rather erect. It adapts well to hedgerow orchards trained in central leader. It shows lateral bearing, but its yield, compared to Chandler, seems to be slightly lower. Late leafing, similar to Franquette. Excellent nut quality, although is not spectacularly large. 100% extra-light kernel. Like its parents, requires high chilling so as not to have growth problems that might affect its yield. Variety registered by INRA (French National Institute for Agricultural Research). Recommended in some cases in which late frosts can compromise the viability of Chandler and also in colder areas of the continent (northern France and England).

Faqs walnut trees for nut production

The criteria for deciding on the type of exploitation to be developed are purely financial.

Producing walnuts means investing in a very profitable crop, with a short-medium term return (beginning of production between the 6th and 8th year), which requires an investment in fixed assets (harvesting machinery, processing facility) that, at the same time as increasing the profitability of the project, determine the existence of a relationship between planting area and profitability (the larger the area, planting area and profitability (the larger the area, the easier it is to recoup the assets that are acquired).

Producing timber implies an extraordinary return (much higher than walnuts) with a long return period (between 22 and 25 years). The acquisition of equipment is not necessary, beyond the installation of irrigation and work machinery (the latter could be leased, in the case of small farms), which means that profitability isn’t so dependent on the planting area. The necessary dedication is much less in terms of time and resources, so professionals from other industries tend to have less difficulty producing timber than walnuts, on land that they do not plan to use for another activity, and that are being revalued each year by the mere fact of having planted walnuts trees (whose value increases as they grow).

In short, if it is necessary to have liquidity in the medium term obtained from our project with walnut trees, it is better to start a nut orchard. If what is intended is to develop a highly profitable “retirement or investment plan”, with almost no risk and very little dedication needed, timber production becomes a very interesting alternative.

Each type of production has its own requirements, which are very different from each other. For example, to produce timber it is necessary to train tall trees (more than 5 m) and with large diameter trunks that are free of wounds from thick branches. However, a French study indicates that in a walnut tree for nut production plantation, for every 20 cm that we raise the lowest productive branch from the ground, we increase nut bearing by one year; in graphic terms to obtain a clean trunk of 5 m tall branches we would have to postpone the first harvest for 25 years! It is clear that both systems are not very compatible. In order to optimize yields, the varieties used nut for nut production have completely different traits to those used to produce timber (in some cases, hybrids with a high degree of sterility, which practically won’t produce nuts in order to devote almost all their energy on producing timber).

Although for Meristec it would be an interesting commercial argument to sell a tree whose timber, after producing nuts for 25 years, has a great market value, we have to discard the possibility of using the same tree to produce walnuts and wood at the same time.

Producing walnuts and timber (in different trees) in the same plantation can be a different situation. Initially increasing the tree density of a farm with the ultimate goal of producing timber using walnut trees for nut production (for example, in a 8×8 m orchard (for example, in a 8×8 m nut production) could have a beneficial effect in the first years (increase in competition, improvement of apical dominance and straightness of timber trees, reduction of pruning and training needs) and allow us to produce nuts until the competition forces to clear (cut) the nut producing trees to maximize the timber decelopment.

In any case, these types of farms are being studied. It is necessary to evaluate aspects such as the influence of the greater growth in height of the walnut trees in the availability of light for nuts, the increase in cost that the use of insecticides in a timber plantation implies that, under other conditions, it wouldn’t need and, ultimately, if the increase in investment is truly profitable.

At present, most of the walnut farms that are being developed have a single clear objective: either nut or timber production.

The answer is very simple: the one that best suits the edaphoclimatic conditions of our orchard. It will depend on whether our climate is very cold, warm, if we have late spring frosts, enough chilling or not, if our soil is limestone, deep, clayey …

We consider it of utmost importance to use the material that works best on our customer’s orchards. It is much easier to get the right plant material for our conditions than to try to adapt the conditions of our orchard (which in many cases may be impossible) to the material that is offered to us.

Meristec has a wide diversity of varieties and clones, both for nut and timber production. If you want to know what material will give you the highest yield in your operation is, ask us for personalized information for free through our technical/commercial department.

In a country with an important agricultural production, like ours, it is strange to have a product with a deficit trade balance such as the walnut. Spain is consuming more than 45,000 MT of walnuts per year and fails to produce even 13,500 MT. It is one of the largest global importers of nuts. The per capita consumption in our country has exceeded one Kg per year, while the average consumption in the rest of the EU is around 200 g. The expectations of increased consumption exceed those of increased production, and the nut produced in our country is more in demand than the Californian nut, with prices that, given their higher quality, remain higher than those of foreign competition. The demand is, therefore, guaranteed.

The walnut is a crop that can be entirely mechanized, from pruning to harvesting; the cultivation costs are around 50% of those of a conventional fruit tree. The nut is also a dry fruit that is easily preserved in agricultural storage conditions, preventing the problems linked to perishable products and allowing commercialization at the most attractive time of the market.

Starting with demand, the trend of the main consumer countries is clearly on the up. Spain is the clearest example: it has gone from consuming 30,000 tons in 2001 to nearly 45,000 tons in 2010. This data makes this country one of the largest nut importers in the world today.

The example is similar in other countries, especially within the environment of the most industrialized countries. The nut is a food whose global demand is growing every day, due to its excellent healthy qualities. The FDA has declared the walnut as a functional food, being the first (and, so far, the only) food that allows labelling indicating that “a diet rich in walnuts can reduce the risk of heart disease”), to the point that the WHO recommends a minimum intake of 0.8 kg/inhabitant per year, which is reached only by 18 countries around the world; in fact there are more than 130 countries with consumptions below 0.5 Kg/inhabitant and year, among which a high number are considered as developed and several of the most densely populated on the planet (Canada, France, China, Denmark , Sweden, United Kingdom or Japan, for example). Everything indicates that the potential for increasing the consumption of nuts in the world is very high.

Reviewing the situation of the main world producers, the largest producer is China (792,000 MT in 2016), but its production does not cover its own supply, as it consumed 807,000 MT in that same year. Its per capita consumption grew by 50% between 2012 and 2016, reaching 0.56 Kg/year, which still leaves room to continue growing. The largest exporter in the world, The United States (California), is the second largest producer in the world (behind China) with 535,000 tons/year in 2016. However, given that 60% of its production is destined for the US market, this means that the world’s leading exporter only sells around 214,000 tons/year, in other words, 40% of its production outside its borders. The position of the third largest world producer has been changing in recent years (2012-2017) between Chile, Ukraine and Iran. Chile is finally becoming established in this position as a result of huge development in this crop. It doubled the area dedicated to orchards between 2011 and 2017, a year in which it had more than 33,000 Ha. Chile is a net exporter of its agricultural production given that its domestic market is not very strong (5,500 MT of walnut in 2016). That means that it is exporting some 19,000 tonnes (2016), which makes it the second largest exporter after the US. Ukraine became the 4th world producer in 2017 with 103,000 MT, but it only exported 12,134 MT (in 2016). Iran has stagnated in recent years between 75-80,000 tonnes and with a very high domestic consumption (exceeding 1 kg per capita and year) higher than its production. In short, of the world’s largest producers of walnuts, which account for more than 92% of total production, there are only 4 countries with a clearly positive trade balance in this product, with net exports among the four of less than 172,000 MT/year of a total global production of 1,708,000 MT in 2016. Only 11% of the world wanut production was intended for exports in 2017. (Data: FAO and International Nut Council Yearbook).

The following figure serves as a graphic summary: if only the developed countries whose nut consumption is less than 0.5 Kg per inhabitant and year were to increase it to 0.7 Kg/inhabitant per year, an increase in production of more than 250,000 tonnes would be needed, which, according to the net export figure mentioned, is virtually impossible for current producers to supply. With this, it would still be below the WHO consumption recommendations. In short, expectations of increased nut consumption are well above the possibilities of increased production.

If we add to this data the factor of being a fully mechanized crop, from pruning to harvesting, with minimum labour reliance, the establishment of walnut orchards becomes an extremely interesting economic activity for the agricultural sector of developed countries.

California is the first world producer of walnuts with a total area of more than 100,000 Has planted that are producing more than 300,000 tons per year (2006). The crop has been developed commercially in that North American state for around 100 years, and the great volume of business generated annually has promoted a great technical development both of the orchards and of the products processing and conservation systems. The Department of Pomology of the University of California, Davis, is the Research Centre that has carried out the most work on the production of walnuts, and which has registered the most varieties in history. In fact, most of the walnut varieties used in modern plantations around the world come from Davis.

However, the volume of exports from the United States is 55% of its annual production. Internal consumption is very high, and continues to grow, boosted by the walnut’s excellent health qualities.

Spain is one of the largest global importers of walnuts (more than 45,000 tons/year), and its main supplier (for more than 80% of its foreign purchases) is, precisely, California. Interestingly, it was Spanish Franciscan monks who introduced the species (common walnut, Juglans regia, L.) in California. In fact, the Californian walnut is the most common one in our shops.

However, many of us have appreciated that certain local nuts, known as “from the country” (which are neither more nor less than nuts produced locally from trees grown from seeds; that’s why they look smaller, or more variable in size, with smaller grain, and darker, both externally and internally) have more and better flavour than California nuts. Even, many consumers prefer them. Why this difference in flavour?

Fundamentally, due to how the Californian nuts are processed. The exporters of that American state are conditioned by the transport method (by ship) that their product needs to reach their main export markets. From the moment the product is harvested and processed until it enters the European distribution channels (its main customers) more than 45 days will have elapsed, a period that will have allowed all local or nearby products to have already been introduced in those channels. Shortening that time entails achieving a better price (market law of all agricultural products), that’s why the California growers try it by all the possible technical means, such as:

- Accelerating ripening through chemical products (derived from ethylene): which causes a decrease in the content of polyunsaturated fatty acids, responsible for both the organoleptic and healthy qualities of this great food.

- drying the nut at a higher temperature (72ºC compared to 40ºC used in Spain), which shortens the drying time to about 3 days, at the expense of excessively heating the nuts, having an effect on their flavour.

They also carry out other processes that are not usual in Europe, such as bleaching (although some countries, such as Germany, have begun to prohibit the entry of walnut treated with this disinfectant).

The final result is a walnut which looks great (good size, very white shell, with no remains of the spots produced by the phenolic content when it is removed) but with limited organoleptic qualities, compared to the walnut that has not undergone this type of processing.

It should be noted that the taste differences described are not due to the varieties used: the Californian varieties produced in Spain, without the Californian processing methods, are even more appreciated than the “country” walnut, because the rest of its characteristics (size, grain colour, kernel performance, hardness of the shell…) are much better than those of seed nuts.

Given that nuts are not a staple food, the consumer acquires it fundamentally due to the pleasantness of its taste, therefore, if they have the opportunity, the national product is opted for before the Californian import, which makes the latter have a market price that even doubles that of California nuts. This data is easily verifiable in any of the hypermarkets we currently visit.

Obviously, advances are made in research, and the most current varieties are developed based on the improvement of traditional varieties.

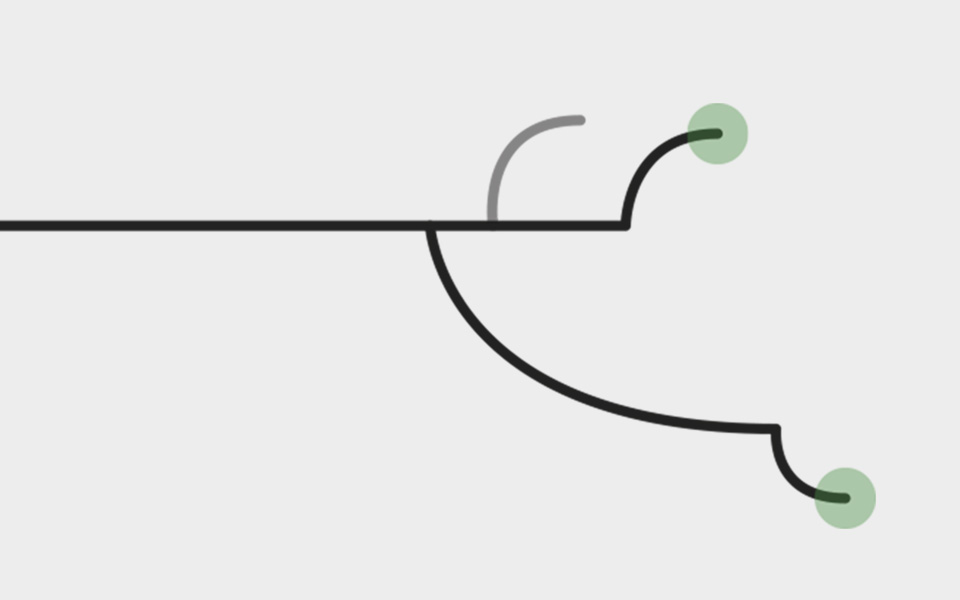

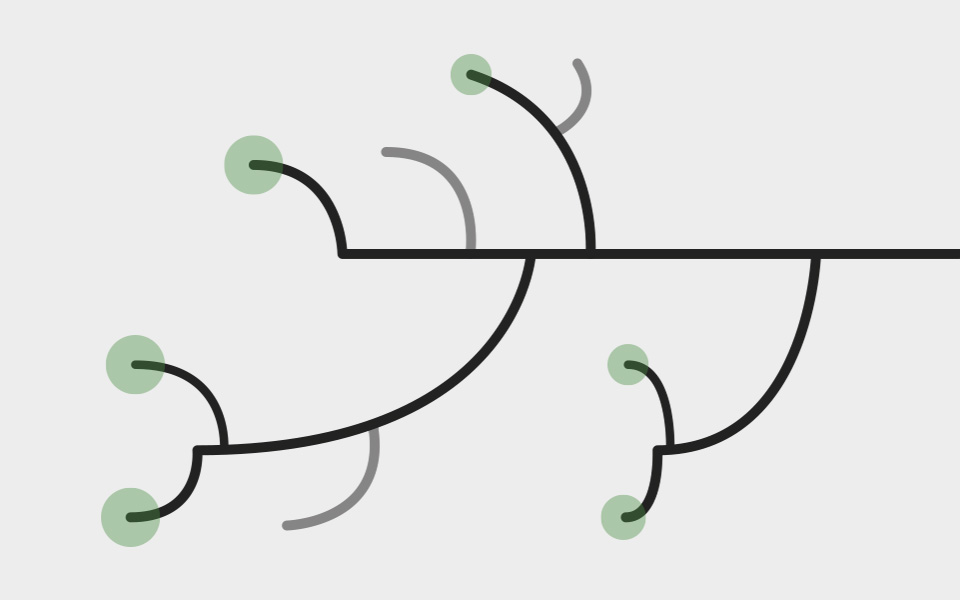

But additionally, there is a productive characteristic that is the one that most distinguishes the productivity of modern varieties compared to traditional ones: the bearing habit, which distinguishes between two types of varieties:

Varieties of terminal bearing: Production occurs only at the end of each branch, in other words, at the periphery of the tree. Therefore, it is necessary to have very large trees if we are looking for high yield. In total, the productive area of each tree is small, so the production ceiling of this type of variety is low (2,500 Kg/Ha, 3,000 in very exceptional cases. Varieties of terminal fructification are Franquette, Hartley, Ronde de Montignac.

Varieties of lateral bearing: The production occurs in the buds that appear along each branch. The productive surface increases, so it is not necessary to develop such large trees for a high yield. When the lateral bearing % of a variety is high, it becomes more suitable for high density orchards. The productive ceiling of this type of variety is much higher, reaching up to 6 or 7,000 Kg/Ha and even more whren the orchard is well managed and under optimal conditions. Therefore, a high percentage of lateral bearing is highly sought after in any varietal breeding programme. Examples of this type of variety are: Chandler, Vina, Howard, Tulare or Lara.

It is worth considering that lateral bearing is a characteristic that occurs relatively infrequently in nature, and that is being artificially preserved in the selection processes thanks to the fact that it is a character of high productive interest for man. Therefore, the vast majority of the plants obtained through traditional seeds will show terminal bearing, offering a tremendously low productive ceiling.

It will depend on several factors:

- The variety or clone to use (for its vigor)

- The edaphoclimatic conditions of your orchard, which will influence the duration and quality of the growth period , and, therefore, the growth period of our conditions.

- Aspects related to management: irrigation availability, fertigation system.

If you wish to consult what the optimal planting frameworktree density for your plantation would be, we suggest you request personalized information for free through our technical/commercial department.